Expedition painting. PART 1

Introduction:

This blog post is long overdue. I’m not accustomed to delivering regular written posts, but I realise the benefit of the process: it avoids over-working anything and actually forces you to finish something.

My recent expedition painting adventures have lead me to explore the history of this phenomenon. My curiosity took me down a deep rabbit hole; expedition painters, diorama painting, taxidermy, history of conservation awareness, war-time camouflage, and adventurous tales of life and death in Africa.

My research at NYC’s Explorers club and the American Museum of Natural History was invaluable, and I am greatly indebted to all those who helped me there. This led me to reading the various accounts of what makes an expedition painter, along with reading from today’s expedition “painter”: The wildlife documentary film-maker, David Attenborough. This all took me on a journey that would bring back the smells and visions of my own adolescent experiences, on my first exotic trip to sub-Saharan African.

Following my experiences painting in the Arctic (as an expedition painter on ELYSIUM “artists for the arctic”) and snorkelling with Orca in the Arctic waters of Lofoten in winter, I have found myself delving deeper into the dynamics of this phenomenon that is the relation between science and art: The history, the people and the process. The artists that have fascinated me are the ones who have straddled this line between the scientific & artistic realm.

By no means can we assume that one can aquire scientific credentials simply from being passionate about the subject. However, I believe a certain scientific literacy and engagement can allow the rigorous observer to collaborate constructively in the scientific realm. I include here Carl Akeley (1864-1926) and his legacy of artists employed at the AMNH, and Louis Tinayre painting for Monaco’s oceanographic instuitute.

Through various exhibitions and lectures, I find myself freshly excited every time I share what I witnessed, what I learnt and what I painted. As an expedition painter, I have come to have a greater appreciation for the artists who have taken on this mission on a larger scale, at very different times in history. Reading of their exploits and researching the various aspects of their process revealed how interlinked their efforts were.

“Little did I know as a teenager, that I would one day be painting the same scenes over 100 years later”

The first expedition painter to inspire me was from my teenage years, as I sat drawing for hours in Monaco’s oceanographic museum, studying and drawing at the aquariums and whale skeletons. On the walls were hanging the many paintings by Louis Tinayre, employed as an expedition painter on several voyages led by Prince and Oceanographer, Albert the 1st of Monaco. Paintings that embraced the great outdoors, adventure, discovery, through their spirit of documentation and faithful artistic interpretation. Two of these expeditions were to the Arctic, in 1906 & 1907. Little did I know as a teenager, that I would one day be standing on the same places, and painting the same scenes over 100 years later.

In my university days, London’s natural history museum was a revelation. Later, as a Florence academy graduate and professional artist, my visits to New York City helped me connect some of the dots between artistic and scientific expeditions.

Firstly: The American museum of natural history (AMNH) with its rich collections and fascinating dioramas. These depict a wide range of staged scenes with mounted animals in front of stunningly painted backdrops, representing a variety of natural habitats from across the world.

Secondly: The Explorers’ club, with past and present members engaged in all manners of exploration, and scientific endeavours. This is where I had the opportunity to closely study some of the original travel sketches for the AMNH’s dioramas.

“New York City helped me connect the dots between

artistic and scientific expeditions.”

With my limited experience, I can only hope to brush the surface on these various subjects. Broadly I’m highlighting how I’ve witnessed the relation between art and science, and researched a selection of active contributors over history. More specifically, I am illustrating the connection between the first expedition painters, diorama painting, and how concerns for wildlife conservation was communicated through the evolving mediums available to it. All this through a personal perspective, my research at new York’s explorer’s club and museum of natural history, and relaying passages from various accounts from the great explorers’ from the past.

DIORAMA PAINTING:

For those who are just discovering diorama painting is, click here to explore the phenomenon through a previous blog post.

In many fields of art, the creative process is often as interesting, if not more, than the actual final piece. The “behind the scenes” revelations often creates more interest than the completed piece. So many I speak to about nature documentaries, refer the BBC ‘s “Planet Earth” series, and love the “diaries” part, almost more than the episodes themselves. The “diaries” reveal the trials and tribulations of filming in the wild. I’ve rarely seen more committed filmmakers.

New York city displays diorama painting at one of the highest levels. But my recent trips to Sweden revealed to me that the Swedes initiated high quality diorama painting before the americans. At a later date, I will expand on my research from Goteborg’s natural history museum.

WHEN WHERE & WHY

“diorama painting would be pointless without sculpture.”

Surprisingly, dioramas would be pointless without sculpture. In America it was sparked off by the mounted animal process, better known as taxidermy. There was a revolution in taxidermy, led by one man: Carl Akeley. Both Taxidermy and diorama painting took on an entirely new life in the U.S. See for yourself, in the following images: Before and after Akeley:

Akeley’s mission was two-fold: Education & conservation.

1. To educate, by familiarizing the public with nature. If they understand its beauty, they will understand its value, and therefore contribute to its protection.

2. To save examples of animals that Akeley feared were soon going to be extinct, due to overhunting.

Akeley went on extensive expeditions to Africa, collecting specimens ranging from lions, buffalo, gorillas, zebra. These were gruelling trips in the 1920’s, with multiple stops and many different types of transport. What would take just a day or two today, would have taken weeks back in the day. I remember flying to Kenya in the 1990’s, with a direct flight from Zurich to Nairobi. A flight time of 6 hours, which seems like pure luxury compared to Akeley’s trips.

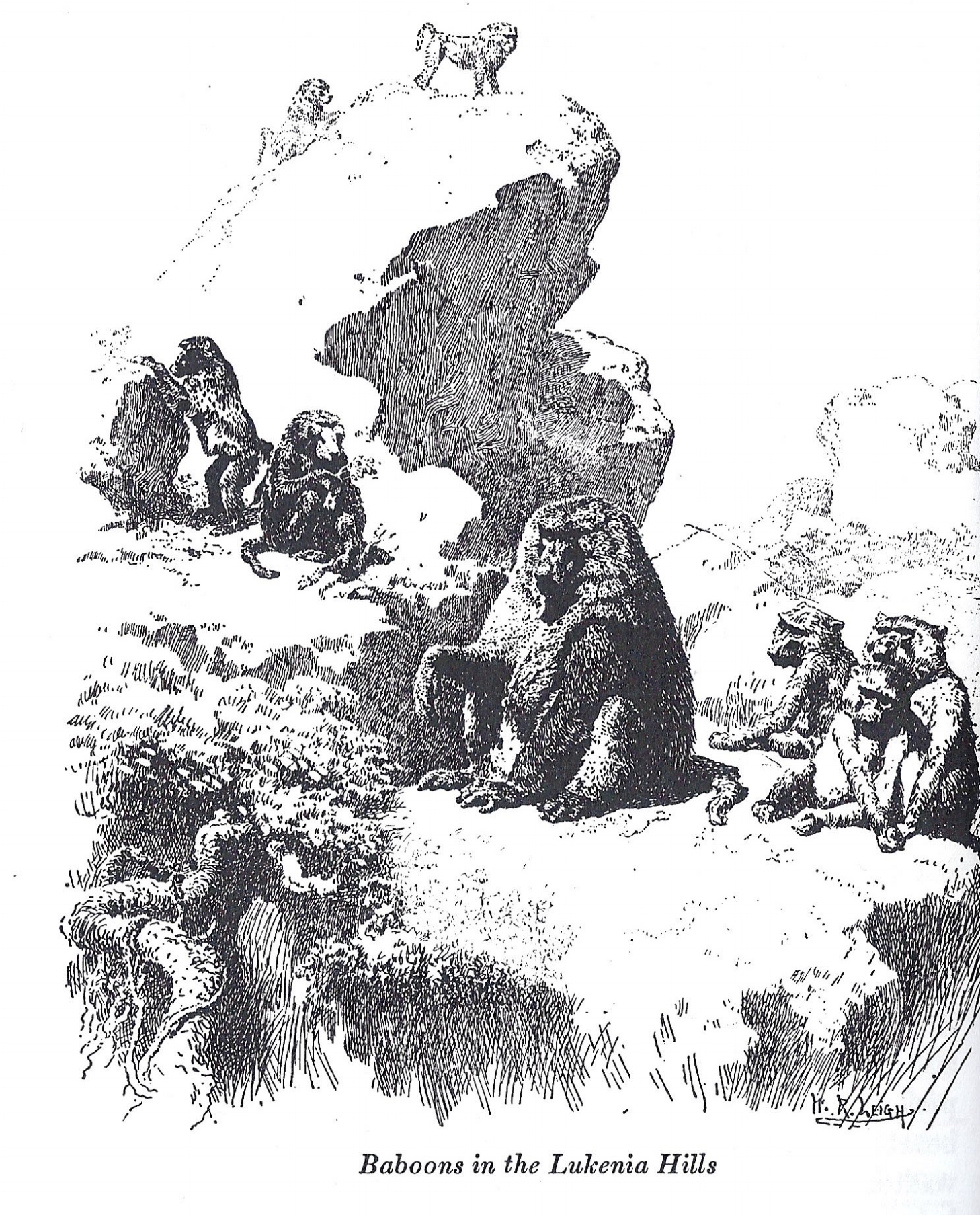

Akeley was quite vocal about his regret in not having a painter accompany him. Facing the beauty of the panoramas in Africa, the camera was not up to the task. The photograph just didn’t capture the sense of the experience. As any painter knows, photography is a monkey’s game! (Just kidding, but what else does this picture suggest?)

Curiosity is sparked, somewhere in Africa, 1920's

Back in NYC, Akeley called out for artists to accompany him. One was Ezra Winter, but they had not come to an understanding. Then Akeley wanted Willard Metcalf (very admired in today’s circle of realist painters) a renowned landscape painter, but he unfortunately died in 1925, before the expedition. This is where the 3rd choice came in: William Leigh. Upon being interviewed, he was hired on the spot, and accompanied Akeley to Africa in 1926.

WHO MADE THEM

(Akeley, Leigh, Browne, Wilson, Kalmanoff, Quinn)

“The museum authorities of those days had an abiding mistrust of the painter.”

Throughout the years, many artists contributed to the design, creation, and organisation of the diorama exhibits. Generally speaking, there were two groups: those who worked out in the field, and those who worked at the museum. Some did both. The outdoor teams collected as much visual information as possible from across the world (see PART 2 “process involved”), and the indoor teams were responsible for enlarging these compositions upon the walls of the museum. I have concentrated mostly on Carl Akeley, William Leigh and James Perry Wilson, as they are the three I have mainly read about up about until now. Some interesting images of in-house painters also include Belmore Brown & Matthew Kalmanoff.

Steve Quinn (one of the latest in-house painter) returned on site in Africa to paint his own view of the gorilla scene almost 100 years after Leigh’s rendition. He also wrote his own account of diorama painting in a fascinating book: Windows on Nature.

The nature of expedition painting required the AMNH to recruit artists for the mission of conservation awareness. The artists of the AMNH are probably the most underrated in NYC. I hope some of the images here (or ones in my previous post) will compel you to visit the museum and see for yourself, or to re-visit it with new eyes.

“The artists of the AMNH are probably the most underrated in NYC”.

With his artistic insight, Akeley saw that all the attempts to depict Africa had failed in one essential- no one had ever conveyed the savour, the feel of Africa: Its tragic grandeur, its savage enchantment. Akeley writes in "Brightest Africa":

“The scientists of fifty years ago (1870’s?) were conscientious, profound, and altogether admirable, but they did not envisage the educational function of museums. They did not perceive the morgue like coldness of their ranked exhibits or the emptiness of their halls..”

“The museum authorities of those days had grown-up with a deep seated aversion of linking science and art. They had an abiding mistrust of the painter. He might provide a delightful source of recreation or sentimental delight, but he represented the antithesis of science.

In this atmosphere of disapproval, a bombshell exploded in 1895. The man who threw it was a brilliant artist who hailed from a farm: Akeley was not afraid to stand alone; he was not timid; he never shrank from battle. He revolutionised the mounting (stuffing) of animals to such a level, that his work could no longer be ignored, and presaged unmistakably the era of the painter in museums.”

This 1926 expedition was William Leigh’s first, but Akeley’s Fifth.

Leigh writes in "Frontiers of Enchantment":

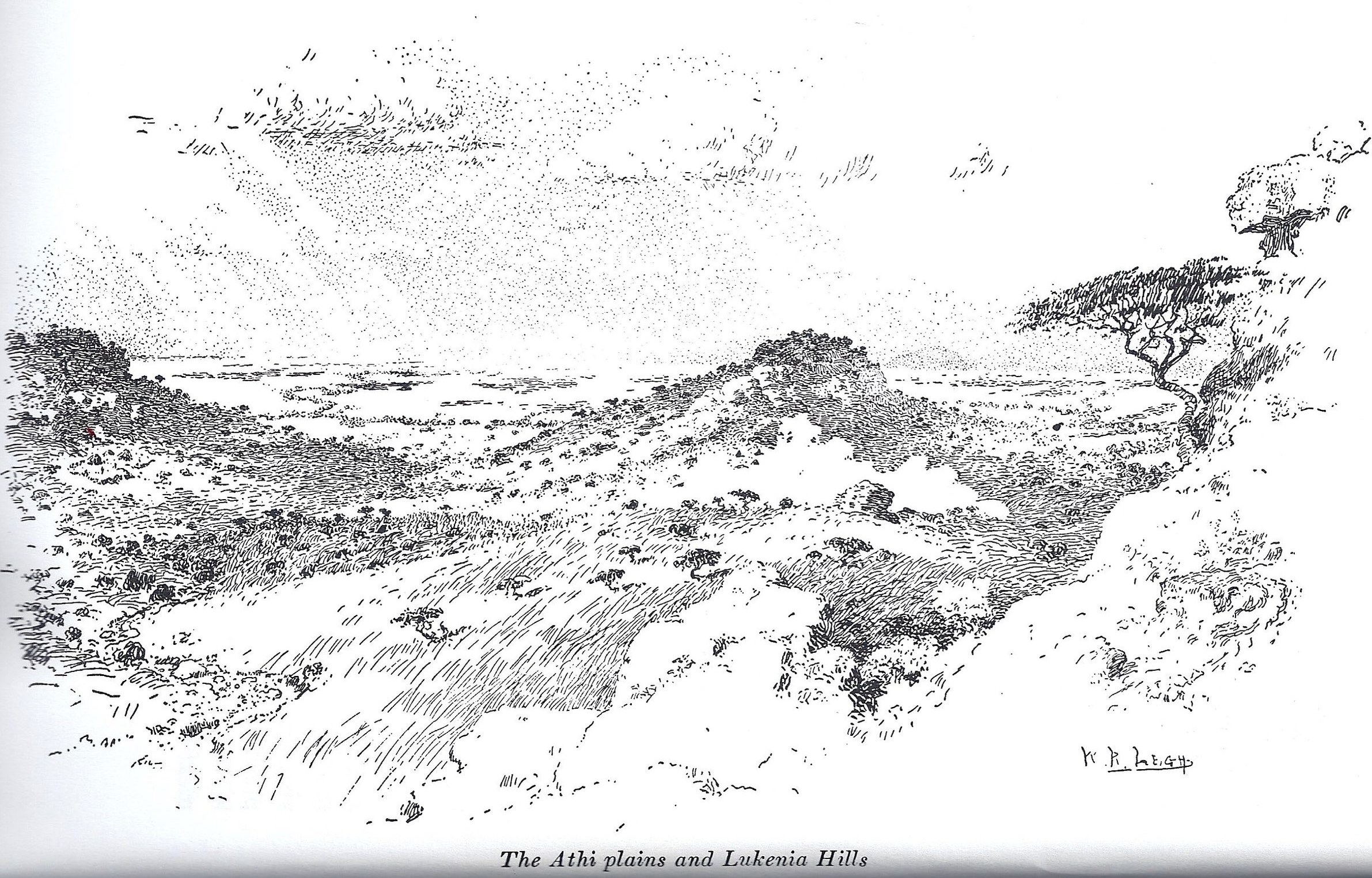

"I was enchanted. For the first time I beheld primitive Africa-the unspoilt, glorious Africa of which I had dreamed. After breakfast I set off to explore the massive pile of granite. Suddenly on the summit of the boulder a little antelope appeared. Immediately I knew I was looking at a klipspringer. My natural history studies had made me familiar with the creature’s appearance.

As soon as breakfast was over, I gathered my boys and plunged into the forest again. I was delighted to find finally find the spot. There was a grand panorama, the white snag, the two volcanoes."

William Leigh's view of the two volcanos, for the Gorilla group. Explorer's club, NYC.

Returning to camp, excited to share the news, he was met by the Dr, who had tears in his eyes.

“I saw Mrs Akeley for a moment, from a distance. She was weeping. Akeley had died, it was 17 November 1926.”

Leigh honoured his great friend in pursuing his work with renewed effort. “I knew what I had to do; organize carriers to get together the paraphernalia I would need for my studies, and to be ready the next morning early to go to prepare my new camp site, some 500 ft higher on the mountainside”

Akeley was a great man – an idealist in the highest sense. He had given his life to pursuing a magnificent idea; he had died a soldier on the battlefield of science

Carl Akeley's Tomb, somewhere in the Congo jungle.

Leigh writes of his approach with collecting visual data:

"When a habitat group of importance is to be done, many studies should be made. One should know the place so thoroughly that no matter what changes are ultimately decided upon, one will be in a position to do it justice.

The painter who thinks he need only make a given number of studies may find that a brand-new conception will finally prevail, and he will be left with insufficient data. He should secure every study he can. He can never know his subject too well.”

Leigh writes of his task facing him in Africa:

"The fantasises of poets or painters become pale and arid when compared to the reality of Africa. The painter or any artist in any medium finds himself bankrupt-totally inadequate. He feels like creeping into a hole. All that saves him is the reflection that, inadequate as he is and his pigments are, no mere man is any better off."

NEXT EPISODE: "THE PROCESS INVOLVED" & "NEAR DEATH EXPERIENCES IN AFRICA".