Expedition painting. PART 2: The process.

"It required straight from the shoulder, honest to god painting, and no nonsense." William Leigh.

As a follow up to PART 1, I am now going to focus on the process of diorama painting, some behind-the-scenes stories, the field work required to achieve these fantastic impressions of Nature. I am greatly indebted to New York's Explorer's club, and the American museum of natural history (AMNH), whose staff were very accommodating and helpful with all my research, allowing me to handle original paintings and go through hundreds of photographs from African expeditions.

Some crucial insight into these historic expeditions also came from reading Carl Akeley's "In Brightest Africa" and William Leigh's "Frontiers of Enchantment". Within these pages, you will find accounts of a painter's confrontation with the elements, reflections on his purpose and his art, and projections of nature's survival. I also further reveal the work of James Perry Wilson, and Belmore Brown.

Where do I start? As usual with these jammed packed stories, there is so much ground to cover that I cannot include it all. I will start with William Leigh's account of his recruitment on Carl Akeley's upcoming 1929 African expedition:

"Akeley told me frankly that he had approached other artists. We agreed that my part in the expedition would be to paint with perfect fidelity to nature.”

Leigh painting in the Athi plains, with his gunboy.

”Most of the time there was clear, sparkling sunshine, never oppressively hot. Under these conditions, to paint the plains with absolute fidelity was no fool’s job. It required straight from the shoulder, honest to god painting, and no nonsense. The fellow who tackled it had to know his stuff.”

“I never enjoyed working more in my life. In Africa I was king, no lugging my paint box, umbrella canvas and campstool myself. I had a gun boy who carried all my luggage, while I carried the gun. when driving in a closed truck, the wet study would be tied in a suitable position and covered with a wagon sheet, thus protected from dust & rain. In the field the boy took the gun, and sat down back of me to keep guard, for in a land like Africa there is never any telling when some creature may start stalking you from behind. At camp in the evening, my gun boy washed my brushes vert efficiently, and this help enabled me to complete many more studies. Sheer luxury, to have nothing to do but paint under there ideal conditions, in ideal weather, and ideal country, just paint, paint, paint!”

I think any painter yearns for this luxury Leigh writes about: eliminating distractions and being able to commit solely on painting. He also elaborates on the style required to attain productive and useful reference material:

“the painter who has cultivated a style or manner is not any good…. The painter must make the beholder forget that he is looking at paint, and feel that he is looking at nature itself. A very high type of artistic knowledge is necessary for this…the artist must forget himself in his work."

“the artist must forget himself in his work.”

“There was something thrilling about being out painting in that wild solitude. The heat was just sufficient to make the paint work beautifully without any thinning medium. To sit there painting in the vast shimmering landscape was ideal. My gun boy would sit and watch. Was he making unfavourable comparisons between what I was doing and what and the paintings he had seen in churches in Ethiopia?”

For the large Serengeti plains of Tanganika (present-day Tanzania), Leigh writes of his specific experience facing his subject. This scene translates into what many see as the epitome of the African landscape. It brings back vivid memories of similar vistas I experienced in the Masai Mara of Kenya.

"My big study was to show the Tanganyika plains from the vantage point of a hillside. At the spot we chose that day, a tree-lined donga zigzagged from the middle ground off into the vastness, joined by other watercourses leading the eye away and away across the yellow immensity, which gleamed pale gold against the lilac at the horizon.

Some of the grass ... seen obliquely from a distance, gave the plains an appearance of rose-yellow or cream in patches.”

“In my picture cloud shadows form vivid bands of wisteria-purple, and kopjes pale into mere shadows in the distance.

On the left a system of hills breaks the monotony of the horizon. Herds of herbivores ascend the hillside towards us, or gather in knots about the trunks of scattered trees, where they are accustomed to rest in the shade and fight flies.”

James Perry Wilson, who worked essentially on the N. American dioramas, was one of the painters who left a strong mark, due to his highly organised methodology. His tour-de-force is surely the Bison group, stretching across three windows, depicting the great migration that is sadly only a distant memory.

With an early interest & training in architecture, Wilson had a very focused manner and deep understanding of how to be consistent in his colour mixing, and perspective drawing. Apparently this seemed to make him unpopular with other painters, being criticised for his cold and calculated methods. Every wall was gridded into boxes to efficiently respect the proportions from the original sketches. They still stand today as a testament to Wilson’s diligent methodology. A lot has been written on Wilson on this blog post….LINK

Below we can see Wilson painting what he needs on site, to gather as much information as possible to create the most convincing illusion back on the museum walls. The result is breathtaking. Notice the distant waterfall to establish a reference from the site to the diorama.

The drawing is very important, and the charcoal underdrawing is highly detailed, allowing the attention to the variety of natural formations that create a convincing illusion.

This bear group has so many parts that deserve commenting on, but the overall sense of light is what always impresses me. It shows how important it is to know how to “key” a painting, to get the most effective lighting out of the materials available.

Another group that hits you when you enter the North American Hall, is Belmore Browne's Alaskan brown bear. This diorama stands at the end of a corridor allowing the viewer to be drawn in from afar. It is probably the most striking display as you enter the North American Hall, and the first one that compelled me due to its grand open depiction of the majestic Aghileen pinnacles and dramatic cloud formations.

The diorama preparations involve a maquette to allow experimentation and problem solving with colour, structure and lighting on a small scale, before committing to the final piece. The maquette could presumably allow the museum administrators the opportunity to judge and approve the full scale version. The background painting was executed before the foreground, and the in-between area carefully arranged to create a seamless transition.

PAINTING FOR INFORMATION

Leigh writes of his process of accumulating knowledge:

"I painted studies that might or might not come in handily. I wanted to pack my consciousness with intimate knowledge of the many facets of African life, and also to carry back as much painted data as possible with which to refresh and guide my memory.”

This is such a striking quote. I see so many art students trying to calculate the sale-ability of doing a drawing, a sketch, a study of any sort. Here you read how Leigh, (who was clearly employed to supply a steady supply of use-able, and completed sketches) would just sketch it all, regardless of whether he could see a direct link to a final product. He would sketch to fill his head with knowledge. Many studies don't need to become specific paintings, but ALL of them contribute to the artist's grand vision. Just look at Turner’s sketchbooks vs. how many are executed as final oil paintings on canvas.

"You can always get more paint. You can’t always get more time."

As far as my own experience in the Arctic, I was constantly reacting to what was happening around me, and recording whatever I could, whether it was in paint, in charcoal on paper, or in pencil in my sketchbook. While you’re in the field, it’s difficult to see what will be use-able later, and what won’t. You don’t have the luxury of hindsight, so the best solution is to be switched on permanently. It proves to be quite a high intensity solution, but you have no idea when you can ever come back, so you get as much down as you can.

When you are reacting to nature constantly, the chances are that you will use more paint than usual, and have a few failures through "wasting" paint. Wasting paint is less problematic or regrettable than wasting time. You can always get more paint. You can’t always get more time.

Leigh writes about painting in challenging but inspiring conditions, and getting help from locals:

"At my camp all went well, but slowly. Often clouds would obscure the view for a whole day at a time. I had to be unremittingly alert, ready to work a few moments whenever possible. Every evening I had to take my canvas well back under the fly, lest rain drench it during the night."

"Raddatz (assistant) attached little pieces of white cloth to certain plants which were to appear as foreground detail in the group, and of each one I made an intimate study in colour."

"One night, seeing Mikeno marvellously lit up by the setting sun. I grabbed an extra canvas, and secured an impression of the peak before the light failed me. I finished the study which is now in the AMNH."

“When I finished my work by dec 11, mrs Akeley suggested that I go at once into the valley…to make a study looking back at the twin peaks of Mikeno and Karisimbui.. So I made preparations for my starting the next morning. Once down at the Barunga camp, the chief was most friendly and invited me to pick out any point I found most favourable…within his domain. I found a conical hill that rose to a height of more than a hundred feet. I climbed it and found it ideal for my purposes.

This Led to the diorama of the Gorilla group There is one diorama that I have been able to witness in all its stages: from fragmented outdoor sketch, to completed single composition, to final application in museum. (I’m assuming the intermediate large single composition that now hangs in the AMNH offices is part of the process, and not an independent commission piece). From explorer’s club, to AMNH offices, to AMNH’s African hall, this view has gone through several processes yet lost nothing of its authenticity.

At Explorers' club, you can witness the paintings that were done in the field. A view across the jungle and Mt Mikeno. They are separate painting, as Mt Mikeno was probably too far off to one side for Leigh to drag it into the outdoor view. Mt Mikeno is the extension of the slope that you see on the right of the jungle view.

In the offices of the AMNH, you will see the enlarged arrangement of the completed view, where all of he outdoor work is applied to one single view. The modulated temperature shifts from warm to cool, and and the overlaps of silhouettes allow for an amazing sense of aerial perspective, convincing the viewer of a huge expanse of space receding to the central volcano and beyond.

The paint application is unctuous even in the far distant hills, allowing some thick textures to express solid forms.

All this work, combined with the efforts of the sculpture team leads to the striking illusion of the Gorilla group diorama.

This is where you can understand why the initial plein-air piece is so immensely detailed, and doesn’t resemble what we are accustomed to see from an “ordinary” plein-air painter. It doesn’t display the orchestration or focus or impressionism that comes through the interpretation of a personal lived experience. This is what initially bothered me, but when I came to understand the diligence and humility necessary for this process, I eventually appreciated and admired them for their greater purpose: “straight from the shoulder, honest to god painting, and no non-sense”as William Leigh put it.

William Leigh struggling to paint in cold Africa

“Back at my camp one morning, I was fortunate in having a clear day, and got well started before the weather changed. It was cold-so cold that I sat with a charcoal stove between my knees, and my paints became stiff that they were hard to manipulate. The wind kept tugging at the fly, and at my canvas, making it teeter and wobble, until I had to sit with my palette on my knees, holding the canvas still with one hand and painting with the other. Fog made the afternoon of the third day quite useless.”

“I had picked the exact spot from which to work: I was raised above the plains high enough to give me a view of them, and still low enough for excellent lines and sufficient bulk to balance the mountains. After lunch I drove back to the chosen spot. I was in high spirits; there was nothing to worry about. I got the whole study ready to mass in as soon as the right hour arrived, when the sun would sink behind the hill before me."

I wish I could write of my painting experiences or results with such confidence.

"Everything developed just as I knew it must. The exquisite island of magical pink, swimming in an opalescent ocean of delicate tones, appeared at the appropriate hour, as if intentionally arranged just for me."

"I worked madly for 30 minutes during which the effect lasted, and when twilight finally closed in, I knew that I had reproduced very exactly on canvas the large impression of which I had been dreaming.”

All painters have their stories of how they pack and travel with their wet paintings. Here’s just one more:

“Back to the car, I placed it carefully keeping it from smearing and dust, tied it securely and covered it with a tarpaulin. Unless a canvas is protected, dust, seed pods, straws, insects will be blown against it. Grasshoppers and ants will crawl over it, tracking green paint from the painted trees all over the sky. Bees and moths will wallow and slop about trying to extricate themselves. Mosquitoes will leave their wings and legs plastered against the most delicate and conspicuous parts.”

RELEVANCE TODAY?

“I will see the sublime spectacle of Kilimanjaro at sunset no more”

One of the reasons I find these dioramas fascinatingly relevant even in today’s society, is how they connect with modern day wildlife documentaries. Outstanding wildlife documentaries like BBC’s planet earth 1 & 2, Blue Planet 1 & 2, are bringing nature into people’s living rooms. Even considering their limitations compared to today’s technology, dioramas aim to do the same thing; Bringing nature as close as they can to people: to the museum and to people’s home. I have the impression that David Attenborough is the modern incarnation of Carl Akeley.

Leigh reflecting on the mortality of a painter, and the immortality of art:

“This picture I paint-which seems important to me, into which we will put all of our sincerest efforts- the best materials extant, with the hope that it will impart some hint of the reality, and endure, perhaps, two or three hundred years-this picture is an ephemeral thing. This soft lump which is I, wielding a clumsy brush-hungering for the impossible-striving to tell the marvels that are before me-this shadow which has to dodge lest the thorns tear and the stones bruise it-will fade-fade faster than the poor thing it puts on canvas.

I turn, the finished study in hand. I am leaving my little hill for the last time- I will see the sublime spectacle of Kilimanjaro at sunset no more. But before I drive off, I take a long look at the mountain. As your light fades, my lovely peak, so will mine; but my record will not change for a while. It will endure for a little time, that those at home may gaze upon it, and maybe, sense something of what I have tried to paint and write”

I was recently reminded of the purpose of central park in NYC (started in 1858) was to make the rural commuters who had left the country to work in the city still benefit from a natural environment that they had left behind. The NYC’s dioramas were there to do more: they were to educate, sensitise the public to the wonder of the natural world, and to appeal to our emotional senses for their protection and conservation. This was achieved by setting up these wonderfully preserved specimens in majestic and believable poses, with realistic & dramatic backdrops to transfix the viewer. It is exactly what contemporary documentaries wish to do on their viewers; captivate our attention, create an emotional connection, and infuse us with a love and care for the animals depicted.

Today’s concerns for habitat encroachment, wildlife conservation, or a pessimistic outlook on nature’s future isn’t so new after all. For those who had the chance to see Africa for themselves in the 1920’s, they had doubts even then.

As Leigh writes:

“Watching these myriad of beautiful creatures day after day, the cogitating mind instinctively asked “how long can this go on? When will encroaching civilization deprive these animals of the immemorial grazing grounds, break up their seasonal migrations, dislocate their scheme of existence and the death knell of the most extraordinary reign of animal life this earth perhaps has ever seen?”

It is the first time a static display ever gave me the experience mirroring that privileged moment of engaging with Nature. The life-like poses, the natural light, the inspiring and completeness of the backgrounds had me hypnotised.

When you have the chance of observing wildlife close –up, you feel an immense privilege of sharing an intimate moment that nature has allowed you to witness. It can be while calmly having your breakfast in the middle of a thousand + migrating wildebeest, or watching a polar bear munching on a seal on the Arctic pack-ice, or catching a glimpse of a falcon dropping out of the sky homing in on its prey as you’re driving down the highway.

It is in these moments that time stops. Eager to share the wonder with another, but at the same time not wanting to take your eyes off the spectacle, in fear of missing a moment of the magic. It is this magic that these dioramas are reaching, inspiring the viewer to disappear into, amongst the dark halls of the museum to become part of the scene.

Da Vinci once wrote: “nature is best appreciated when shared.” Generally,I have found this to be true, but the lone experience is somehow purer. Without the need to validate the event itself with a companion, the experience of a lone exchange with wilderness somehow opens a powerful bond with our ancestral heritage.

NEAR DEATH EXPERIENCES IN AFRICA.

The reality is that people only come into dangerous proximity with the wild, due to human settlements encroaching on wild territories. In most situations, wild animals will avoid humans, and avoid confrontation. Contact between the wild and human populations also happens when young animals are compelled by curiosity to come too close. Occasionally surprise or panic can spark off a defensive reaction, which can then lead to unfortunate consequences for both parties.

When you throw hunting into the mix, then no-one can be surprised at the consequences, especially when you decide to hunt predators. For the sake of science, these hunting trips were not for the faint hearted. It is important to point out that they are incomparable to today’s dubiously financed, chaperoned, hand-lead, thrill -seeking, point blank range, holiday trophy “hunters”.

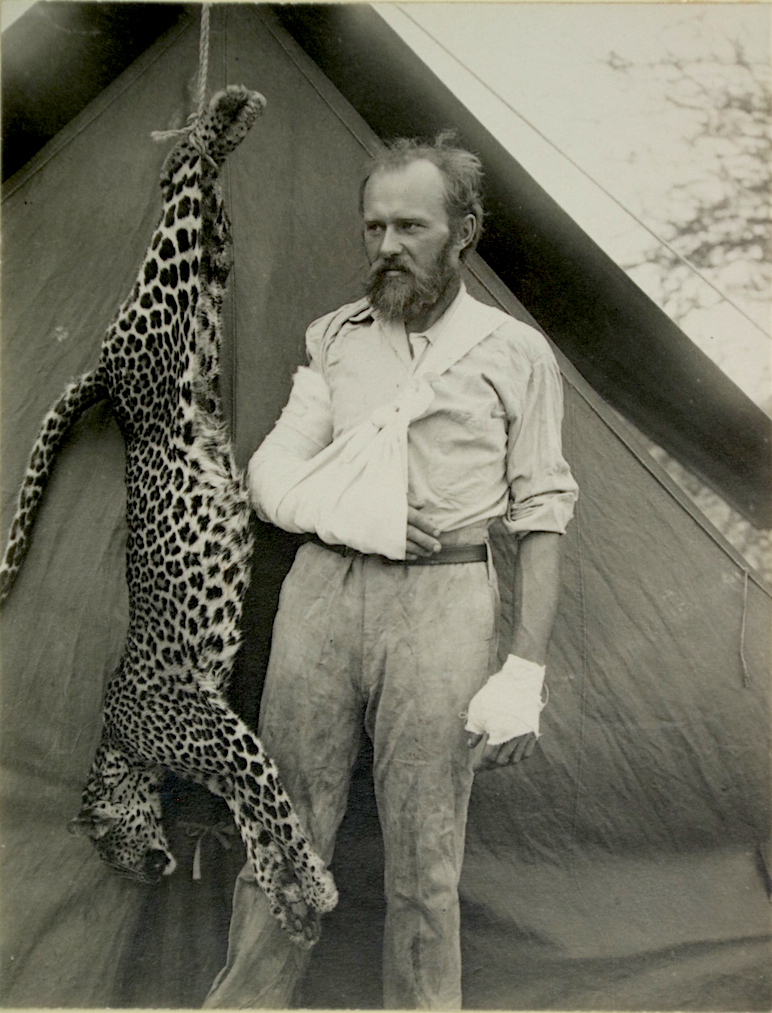

“A leopard, unlike a lion, is vindictive. A wounded leopard will fight to a finish practically every time…”

On a specimen collecting outing, Akeley spots a leopard. He manoeuvres to get closer. He has it in his sights, but it’s hiding in the brush. This not the ideal angle, but he has to try. With his rifle, he manages to shoot it, but only catches its hind leg. Most animals seek to retreat to safety from humans, and especially when injured, but this leopard decided to break the “rules”.

As Akeley desperately tries to reload his rifle for the final shot, the wild cat comes out of its hiding spot, and launches itself towards him. The leopard is on him in a flash, the rifle goes flying, and Akeley is pinned to the ground. The intimate death-lock is such that Akeley can smell its awful breath.

“The rifle was knocked flying, and in its place was eighty pounds of frantic cat!”

These cats have a habit of holding down their prey in their jaws, and slashing at their torso with their hind paws. If the leopard’s back leg was not injured, Akeley would be disembowelled by now. But the hind legs can’t quite carry out the attack.

Akeley is faced with a desperate choice. Keep getting slashed to pieces, or do something radical to tip the balance in his favour. With no weapon left, he uses his bare hands.

“she struck me high in the chest and caught my upper right arm in her mouth…. With my left hand, I caught her by the throat. Little by little….I drew the full length of my arm through her mouth inch by inch. I was conscious of no pain, only of the sound of the crushing of tense muscle”

"For a moment there was no change in our positions, and then for the first time I began to think and hope I had a chance to win this curious fight. Up to that point….I had expected to lose.”

Akeley decides to save himself not by wrenching his arm free, but instead by pushing his fist downwards, deep into the leopard’s throat, in an attempt to suffocate it. The battle continues until exhaustion

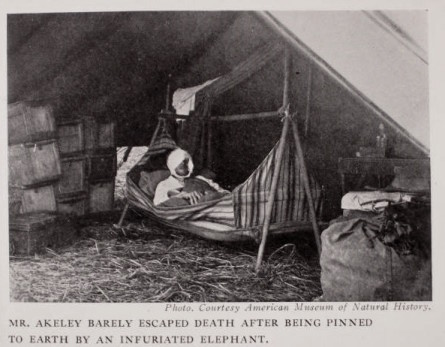

Akeley is a mess, his clothes all ripped, his arm all chewed up, covered in blood and dirt. He staggers back to camp, his companions jump to their feet, and rush to treat him, in particular the potential blood poisoning:

“the antiseptic was pumped into everyone one of my tooth wounds until my arm was so full of the liquid that an injection in one drove it out of another”

This encounter happens very soon upon his first African trip, and he makes sure never to get quite so close again. Akeley’s encounters with elephants prove to be even more dangerous, and Leigh’s illustrated accounts of elephant attacks are quite terrifying, as are the stories of Buffalo and Gorilla.

Akeley writes of his expereince with elephants:

"Usually when an elephant kills a man, it will return to its victim and gore him again, or trample him, or pull his legs or arms off with its trunk.”

“In spite of his appearance, (the elephant) can… move through the forest as quietly as a rabbit.”

Akeley recounts the unique nature of the vicious Elephants of Kabale.

“Due to the native’s hunting in this area, the elephants were unusually vicious. The elephant’s technique of attack is first to fell his victim with a blow from his trunk. He then kneels and gores it with his tusks, after which he macerates it with his front feet. Next he picks up what remains of his enemy and flings a hundred feet away. Finally, he walks around in a circle for perhaps two hours, watching to see if the victim stirs. If it does, he returns to gore it again”

Akeley shares his ambiguous impressions of the Gorilla. By all accounts, he struggled psychologically with the hunting of the Gorilla. He did not hunt it frivolously, neither did he dismiss his kinship with it.

"The gorilla. He seems a Neanderthal man-a remote kinsman, whom you would instinctively hesitate to slay because it would seem too much like murder.

"The man-ape arouses in you a psychological reaction no other animal produces. Strange fancies race through your brain. Is this what we looked like a million years ago? He utters a roar of wrath which has a haunting resemblance to the bellow of drunken dock hands whom I have seen fighting on the new York river front."

FINAL THOUGHTS.

Whether it’s modern day wildlife documentaries, or dioramas from times past, I feel the message is channeled though the same medium: Visual beauty, story telling and shared experiences with nature. Nature is the great equaliser.

The reporting and witnessing of nature, the sharing of the lived experience helps to inspire us to care, and to feel connected to something greater than ourselves. Everything civilisation has ever designed has been inspired and sourced from nature, from architecture through technology to medicine. Our connection to nature and history is something that can bring real perspective to understand our place and role on our planet, to remind us our stewardship of it.